As Wikileaks first released 70,000 documents from the war in Afghanistan – and then a staggering 400,000 incident reports on Operation Iraqi Freedom, it’s become clear that great sources today means something different than waiting for Deep Throat to call. The question is if old media is up for the challenge?

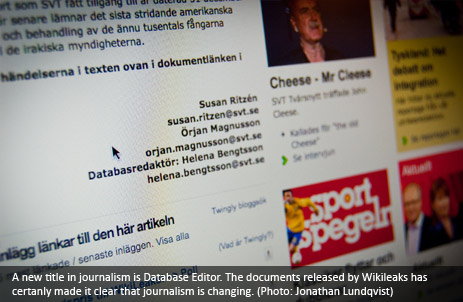

The Swedish national television network, SVT, was one of the few news organizations invited by Wikileaks to get advance access to the data. Apparently, SVT has a dedicated database editor employed! This is not news for larger, international outfits, like The Guardian, but to my knowledge it’s a first in Sweden. It’s a move that must be applauded, and hopefully this will inspire others to follow.

Understanding data is crucial for journalists and needs to be a prioritized part of the job – and it’s really nothing new. Scientists, even in social and political science, have always been looking at the world through datasets. For them, data mining is a methodology for finding patterns, discrepancies and that particularly interesting angle that’s worth a closer look.

The data is the story, stupid!

In the Wikileaks case it is, of course, quite obvious that a journalist printing nearly half a million pages and, after a quick visit to the coffee machine, start reading from page one is going to fail – and fail miserably. But it doesn’t have to be a massive material like this to make a data based process worthwhile.

In a transparent world, all data – in its raw, true, unedited state – would be made available to the public. The good thing is that the world is potentially filled with people qualified to do such analyses, and where journalists would fail or don’t find that needle in the haystack, maybe someone else will. Because the data is there, for everyone!

The data is the insight, stupid!

There is a tendency to treat whatever knowledge or intelligence is built up within an organization very secretively. In the end, the world has silos of insight, but no way of connecting the dots.

As I see it, there are two ways of looking at it. Firstly, from the point of transparency. This is what scares people, because what if someone finds something to complain about? There’s a tendency to treat data like business secrets, and reserve exclusive right to interpret the data. Transparency is naturally most important for anything governmental, but in that sector at least we can legislate for openness. Doing so for private enterprise is much more difficult.

Secondly, and this is what I believe people are missing, is that data mining and auditing by a third party can actually help the organizations’ internal processes. It will make them smarter; it will help them get better at whatever it is they’re doing. It will help companies churn out better products and better services.

There are, for example, a lot of NGOs that should open up their projects and submit its data of statistics, knowledge and insight for general use by external parties. Not because they have to, by law, but because they would gain from it.

Charity organizations are also dependent on donations, and it’s reasonable to think that donors have the right to know exactly how their money is spent. Understandably it’s scary, but the question is if they can afford not to do it in the long run? What if the donors would require it to make a donation? It’s the route that the UN is taking, for example.

The data is the giant, stupid!

Once data is set free, it can be combined and cross-referenced with other data. It can be plotted to geographical information system or provide answers to questions the creators never imagined. Suddenly, a seemingly dull dataset gets new life, and can possibly be used for something that wasn’t imagined by its creators.

Hans Rosling, professor of public health, and a fantastic public speaker at that, combine UN data, and fight for more open data, and gain valuable insights that would have been impossible to attain in any other way.

Data owners must realize that they are the giants on whose shoulders people want to be standing.