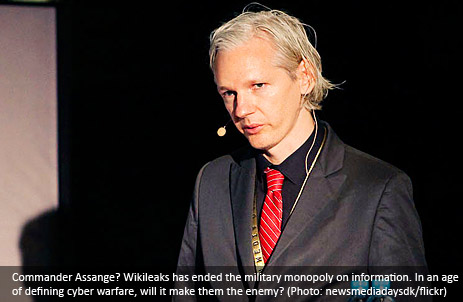

Pentagon, with its newly founded US Cyber Command, is going all-in against an undefined enemy, with fear-mongers on the sidelines crying for blood. The state of the world being as it is, the question is if Wikileaks is going to be the first victim of this new offensive force.

Wikileaks, maybe more than anything else in the last decades, has changed the rules of the game. Whilst using the Internet to anonymously disseminate material is nothing new, the systematic release of classified information is. Quite understandably this is a major concern for the American military might.

Our system, based around the existence of sovereign nation-states has been relatively stable since 1648, when the Peace of Westphalia was signed into effect. It might not be a perfect fit, due to its territorial focus, but it’s the best thing we have to define and manage our world.

War on a Changing Arena

The concept of international security has evolved greatly in the twentieth century, changing from issues around the immediate military needs to a much wider and all-encompassing definition. The older definition is a narrow concept of security, where state actors dealing with military issues – for example the Cold War-era military tension between the west and the east.

A wider use of the term, however, also includes other issue as well as other actors, thus making it possible to, as an example, consider the spread of AIDS, or a coming bird-flu pandemic, to be an integral part of international security. However, the use of a wider definition also found critics among the more traditionalist researchers over a fear that the meaning of the term would be diluted.

While the rest of the world abandoned using the word “cyber” sometime back when Clinton was president – at least when not referring something out of a Bruckheimer movie – this is not true for some military theorists. The idea is that there’s a cyberwar on the just beyond the horizon. Some very loud voices are claiming we’re already knee-deep in it.

Without much public debate, the US Cyber Command began its operations in May of 2010, following a sense of urgency in defense circles of a very real and imminent threat. (Or maybe, as some would put it, there is a lot of money in pushing that agenda.)

The USCYBERCOM shoulder the responsibilities from several other branches of the US forces to “conduct full spectrum military cyberspace operations in order to enable actions in all domains, ensure US/Allied freedom of action in cyberspace and deny the same to our adversaries”.

The Press as a Pillar of a Free Society

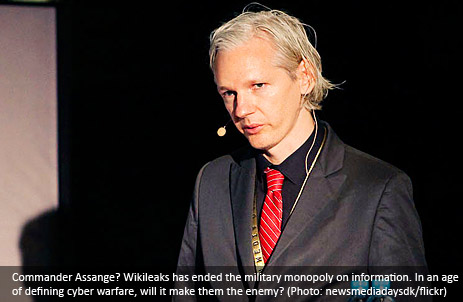

Wikileaks crushed, with a few swift blows, the information monopoly of the military. “Truth”, says Julian Assange, the site’s founder and iconic spokesperson, “is the first casualty of war”, repeating a truism that is rarely backed up with hard evidence. Going through the material, the cliché was proven. Not only did he documents show many things that were never reported, but it also showed outright lies and distortions.

With a very broad definition of security, the free press will be at stake. It goes without saying that exposing certain truths about how we wage wars; on the justifications or actions of troops, is a security problem for the military – and the long run, also for society. But, wait, why if so, do democracies have a free press?

The free press was created, in the liberal western world, as a vent. When the reformists set out to create a new egalitarian society, they deemed it necessary to protect the people from the state. One way to achieve this was by giving the people a way to scrutinize those in power.

Historically, one could blame the press for many wrongs, but at the same time they must be commended for being pivotal in many of the biggest shifts we’ve had every since: from the abolition; universal suffrage; the civil rights movement, to; Watergate. Without overstating the importance of a free press, it’s quite clear that corruption is much more common where the press cannot oversee, comment and criticize people in power. The vent is needed to protect the society from itself.

For the people being scrutinized however, the press can be a real pain in the ass. Consider for a moment the Vietnam War, where journalists had quite good access to the battlefield – and to the soldiers. The stories, images and films are to numerous to mention. It pretty much blew up in the face of the military. It was impossible to keep the general public at home in favor of a war that didn’t portray the solders like heroes, but rather the opposite.

Looking back it’s tempting to say that it seems like it’s impossible to win a war if you are not allowed to commit atrocities. But, the problem is that the people don’t like atrocities. They especially don’t like to see dead children when they’re having breakfast. So, the military came up with a new plan. Starting with the second Gulf War they embedded the journalists systematically.

By doing so, they could control what happened, the journalists were spoon fed information and given selective access. As an added bonus it experiences showed that the embedded journalists became surprisingly favorable to their embedders.

Controlling information and spinning events became paramount to keep be able to maintain support at home. And support at home is a prerequisite to keep fighting. So, the part of the mission is to always make sure the military is in control of the setting, because the context will decide how people perceive events. The war must be justified – and justification can be spun. At least, it could.

War is Peace

Richard Clarke, former advisor to the White House and author of the book Cyberwar, proves my point already in the title of his book. “War” is diluted to the extreme. His book has been widely criticized for being dishonest in many of its descriptions of supposed examples of cyberwar.

Clarke tells a story about a dystrophic future where Chinese hackers take down the Pentagon’s networks, trigger explosions at oil refineries, release chlorine gas from chemical plants, disable air traffic control, cause trains to crash into each other, delete all data held by the federal reserve and major banks, then plunge the country into darkness by taking down the power grid from coast-to-coast. Thousands die immediately. Cities run out of food, ATMs shut down, looters take to the streets. Sound familiar? You’ve probably seen the plot in some bad movie.

Even Clarke descriptions of historic events are flawed. Just five minutes on the Intertubes would have given Clarke better explanations: He claims the Slammer worm was responsible for the blackout in northeast of US of 2003. The Energy Department concluded otherwise. A power outage in Brazil is also attributed to a hacker when, in reality, it was sooty insulators that was to blame.

The danger is to attribute everything from teenage hacking to industrial espionage to “war”. War, at least as most of us perceive it, is a premeditated act from a state-actor, not acts of autonomous people or groups.

Just like the War on Terror before it, the term Cyberwar is not coherent. The objectives are unclear – so the war can never be won. There is no last battle.

There’s a dark side to this new rhetoric. It makes us think of war as a natural state: we’re always at war; war is all around us. It makes us think of peace as an anomaly. It implies a low-intensity war that becomes part of the fabric of our society – and makes us accept fear and suspicion as a part of every day life.

Wikileaks in the Crossfire

The introduction of a new domain for warfare is a premeditated aggressive move. The big question is how it is going to be used, and what doctrine will limit its application. And, how will other countries will react to network attacks by conducted by a nation-state.

Wikileaks is clearly a threat to the military, in their view. Remember the vague scenarios described by Clarke. Wikileaks, even though it is only the messenger – in the same way that newspapers were when it published the Pentagon Papers – has attracted attention from the power structures, and they’re not happy.

Julian Assange has been portrayed as an enemy of the state, responsible for jeopardizing the security of thousands of US servicemen. Of course, the fact that he caught the military with its pants down isn’t helping him. The action could, from the American perspective to be a defensive move, to protect national secrets to be blown out of the water.

One possible scenario is that Wikileaks gets attacked, in order to take it down. Beside it being a practical impossibility to take all the copies of the material down (simply due to the nature of the Internet), what would be the implications if USCYBERCOM attempted to bring the main site offline? At least parts of the site is hosted in Sweden, and to make things even more complex, Wikileaks are possibly even hosted under the protection of a political party with representation in the European parliament.

An attempt to bring the site down would be a clear breach of international law, and of Sweden’s sovereignty. It would also be a carte blanche for a whole new doctrine in international affairs, and essentially undermine the Westphalian system.

The principle of freedom of information is very important to treasure. It dictates that while we can punish the Daniel Ellsbergs and the Bradley Mannings of the world for leaking classified information, we cannot prosecute those who simply distribute, print or discuss the leaked material.

It would also be an all-out War on Journalism. And then we have to ask ourselves: how may people have died in wars defending that very freedom we now wage a war to destroy?

(Thanks to: Copyriot, DN)