Supporting Digital Democratization?

The recent race to fund, what is generally described as, democratizing technology made me go back and re-read an article from last fall. Written by Sami Ben Gharbia, a Tunisian exile based in the Netherlands and the Advocacy Director of Global Voices Online, it has the cumbersome—but quite informative—title The Internet Freedom Fallacy and the Arab Digital Activism.

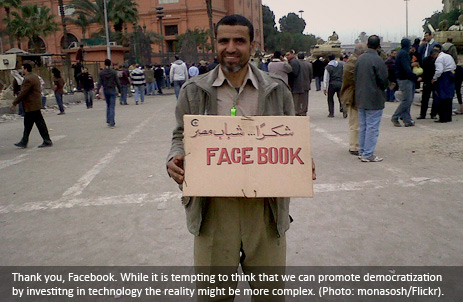

It’s truly an interesting read in a time where world leaders (and pundits) are trying to understand and explain what forces set off the avalanche of protests in the Arab world. A very common explanation has been to attribute a lot of credit to the new media landscape – and also to services created by western companies, such as Twitter and Facebook. Even though some weeks have passed, we’re pretty much in the eye of the storm, and it can be difficult to maintain perspective on everything that happens.

Interestingly enough, Ben Gharbia’s article is about the relationship between the activists and the western countries, written some six months before the revolution. At least to me, that puts some extra weight behind his arguments. Basically, he questions whether or not active western involvement in providing certain services are beneficial or if it is, at worst, actually hurting the very same struggle it sets out to help.

Follow the Money

My renewed interest in this topic—apart from being pulled in by the gravity of inspiring change—comes from the government pledges in the months. Millions of dollars have been earmarked for the struggle of Internet freedom and free speech online. Internet activists are the new revolutionaries; the sparks that lights the fire of democracy, it seems. Hillary Clinton made them part of the US foreign policy and the Swedish government where quick to follow.

I took part in a meeting at the Swedish Department for Foreign Affairs where representatives from the private sector, NGOs and academia. At the request of the Minister for International Development Cooperation, we were invited to discuss the need for support to Internet activists and how the Swedish government could assist in such matters. A vocal part of the group were entrepreneurs who were restless to get going with services in democracy’s favor. While I certainly applaud the initiative they show, I also maintain that the fearless quality often associated with venture capitalists might be difficult—and risky—to apply to development projects.

No Good Do-Gooders?

With some insight from the traditional NGO sector, I know that spending the dollars wisely is of uttermost importance, not only for the “investors” but also for the recipients. While there are many terrific development projects across the world, rest assured that they didn’t come about by chance. They are the result of a lot of smart people’s hard work and experience – some drawn from a lot of very costly mistakes.

The international “aid industry”—to use a quite derogatory term—has a history lined with failed projects. Some of these projects were small – others were enormously huge. At best, failure meant that money flushed down the toilet. At worst, it destroyed lives, societies, resources or infrastructure for decades.

Some secondary effects of the failures were even worse as it dented people’s trust in the institutions – both on their and on our end. Such mistrust is deeply unfortunate as it damages any opportunity to build strong civil institutions because they are—you guessed it—based around trust.

It is humbling to remember is that also disastrous projects were designed and implemented with the best of intentions.

Designing successful development projects, regardless if its support of an advocacy group, human right or humanitarian work, is not something to be taken lightly. In private enterprise, venture capitalists risk their own money. Nothing more, nothing less. If a product fails, the VC walks away with a little less money. If a development project fail, the consequences for people can be devastating. Say a routing protocol designed specifically to help Iranians circumvent their Internet blocking would be compromised, and thousands of people would be jailed because of it, can we just shrug and say: “Ehum, well, we tried!”?

Always remember that simply wanting to do good is no guarantee that you will do good.

My Unordered Checklist

While I realize that I might seem hesitant to the benefits of development aid, I can assure you that is not the case. But, one has to remember that it has it’s own logic, just like any area. I’ve outlined a few points, specifically with regards to Internet projects, that I think should be considered with great care.

- The beneficiaries should initiate projects. Trust people’s inherent capacity as well as their ability to know what’s best for them. Don’t master them or push technology or ideology down their throats. That would, more often than not, do more harm than good.

- Maintain a network that’s free and neutral. Political ideology is not basis for discrimination – it will only bring suspicion. Live by the values you preach and differentiate the medium from the message.

- Encourage strong civil institutions. They weave networks of trust between people. And trust build nations.

- Ensure sustainability. External support is always finite and the project must be designed to keep going, even after you’re gone.

- Last, but certainly not least: Work to fulfill the rights of people, rather than the needs of beneficiaries. Use a human rights based approach. Use Article 19. Live by it.